Historically I’ve best connected with visual art aided by language. I remember the first time feeling a painting had “opened up” to me—it was my sophomore year of high school and we were on a Girl Scout trip to London. O the dorky but it was gonna look choyce on my extra-curricularly-challenged college apps, and it enabled me at age sixteen to “go abroad” (as I’m sure we called it then because we were your stan-pro Liz Bennet-obsessed adolescent girl-nerd anglophiles) with my two besties Liz and Teri. Whatever you may say of the Girl Scouts, those bitches know how to make an itinerary—the scope and efficiency of our touring was creepy-cray. We saw a lot, and it was a formative trip in many ways (like we discovered brie, tomato, and basil on baguette, which would become the staple sandwich of countless picnics back in the Hubs), but I especially recall our visit to the National Gallery.

Our tour guide inspired instant worship in we three—she was sharp, articulate, clearly cool, and a very smart dresser in knee-high high-heeled boots and an expensively-cut pencil skirt (I actually wonder if she was a partial inspiration behind Hagen’s eventual pursuit of a degree in Art History). Passing some umpteenth altar painting she halted the group to provide perspective and context, explaining that a parish would scrimp and save to purchase one such painting, which would likely be the only fabricated image its congregants would ever see (books were wildly expensive and peasants had no access to their illuminations and illustrations). Viewing this rendering of a religious scene was so singular and profound in the lives of the parishioners as to almost give literal flesh to the biblical figures whose stories the worshipers had endlessly heard and imagined. Our guide went on to describe the vast murky old churches, their cavernous transepts darkly lit by the light of many candles, and how the flickering flames playing on the canvas’s oil-painted faces gave their subjects' complexions circulation, their black eyes inhabitation, as if the subjects' spirits became in the artwork actually incarnate.

Sister Wendy is of course the utter shit and was also tremendously inspiring for me, showing me that paintings could be as tricky and trap-doored and treasure-troved as poems (which I was at this teenaged point well-versed in the pleasure of explicating).

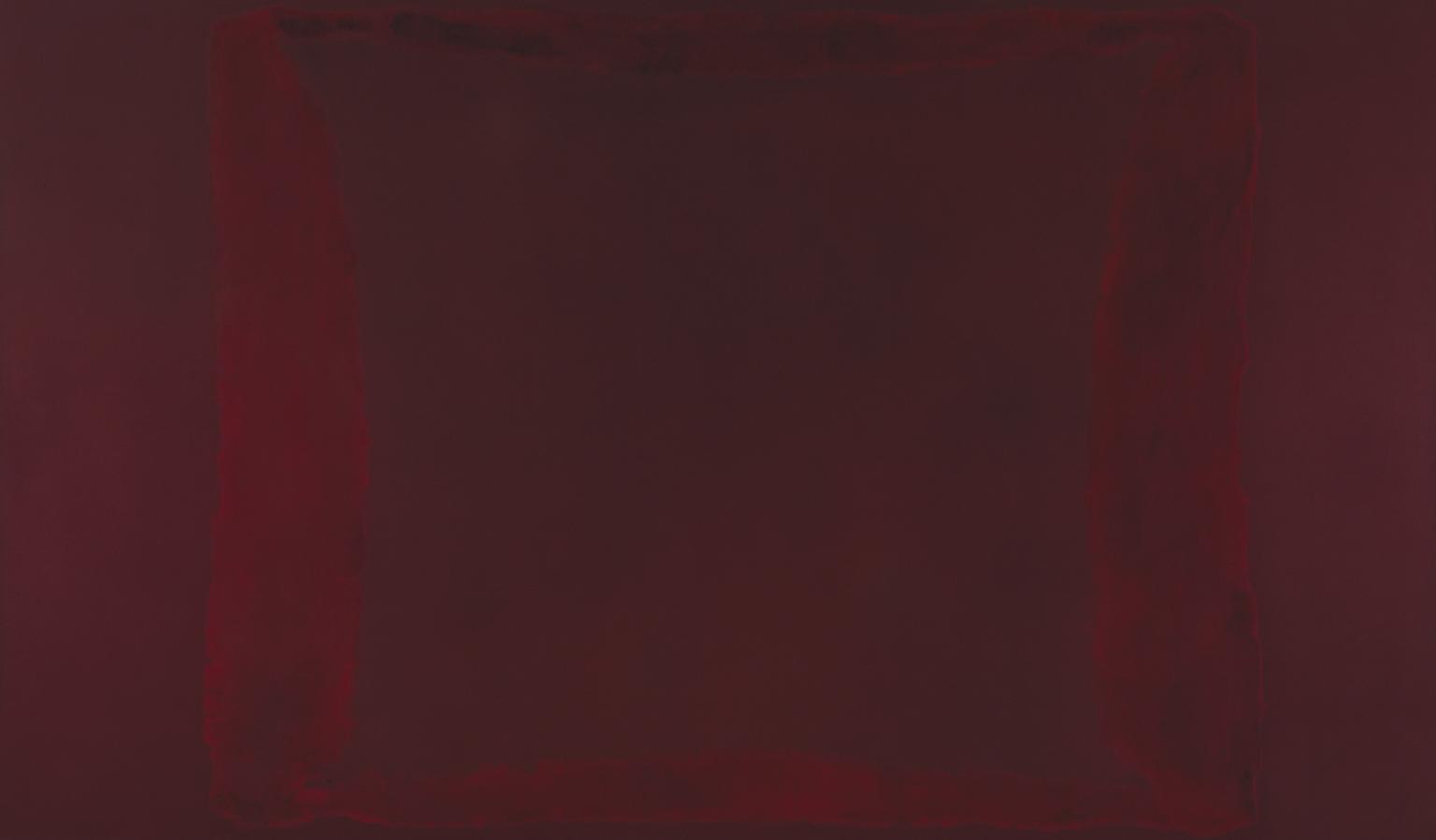

Memorably revelatory as well was this PBS Rothko doc I’d come upon my mom watching one night. It’s got those some of those cheesy public-television “dramatic reenactment” elements, but I was struck by the capacity of these abstract painted works to catapult the show’s host—Simon Schama—into remote cosmic zones. Schama, recalling his first time wandering into Rothko’s remote and darkened room in the Tate, relates:

And there they were, lying in wait…Something in there was doing a steady throb, pulsing, like the inside of a body part, all crimson and purple. I felt pulled through those black lines to some mysterious place in the universe.

Revisiting these same Seagram mural paintings decades later, Schama meditates:

Look at this one. What do you see? A hanging veil suspended between two columns? An opening that beckons or denies entrance? A blind window? For me, it’s a gateway. If some of those portals are blocked, others open into that unknown space that art can take us, far away from the buzzing static of the moment and toward the music of the spheres. Everything Rothko did to these paintings, the column-like forms suggested rather than drawn, the loose stainings, were all meant to make the surface ambiguous, porous, perhaps softy penetrable. To a space that might be where we came from, or where we will end up.

Holy god yes! The doc’s worth a watch, and left me with the lasting sense that an image could transport one to transcendence in ways I’d previously experienced only through music and literature.

It wasn’t ever assumed that I would turn out to be any kind of “creative”—from young’n times careful, bookish, and inquisitive I was plugged soundly into the “Scholar” pigeonhole. That didn’t really pan out in the Ph.D. pursuit we’d all vaguely assumed it would, and now it’s difficult to imagine it will. But I feel good about that. I like the tentative and gentle wavelength I’m operating on these days, and taking pictures is what has helped put me here. I’ve touched on it before, but I was massively stymied around writing for a lot of years. In new journals I ripped out single-sentenced pages until I literally de-reamed the bindings. It was loco and awful.

I would not be exaggerating if I said that for a handful of años my single meaningful creative outlet was making outfits. This was exacerbated in every direction by my ex, who much of the the time regarded me as an “attendant lord” (crossed with an Ophelia) to his Hamlet, the best supporting actress to his capital-H Hero, even at times as a decorative accessory; he would literally pay compliments like, “That’s a really good girlfriend outfit.” You osmose that shit even if you think you’re too smart for it—you do. And it’s too easy already in our mind-bogglingly gob-smackingly patriarchal misogynistic objectifying world.

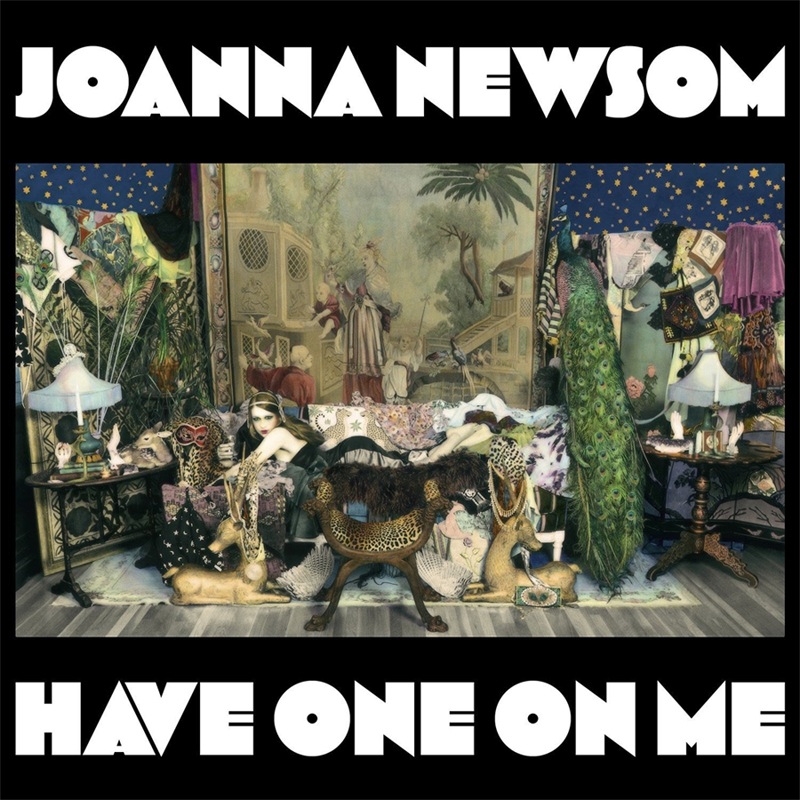

This is a lengthy aside, but I’ll bring it back around: I think this is one of the major themes running through Joanna Newsom’s feather-footed behemoth of an album Have One On Me. The record’s protagonist is suffering from a crisis of selfhood, that probably has partly to do with her troubled relationship with an objectifying and unavailable pardner.

The title track’s mistress to the king, Lola Montez, is all frou-frou razzle-dazzle feminine seducery in her floating skirts and “handsome brassiere,” and is, as it turns out, utterly disposable—or "expendable."

In “Go Long”—another favorite off the record—the song’s protagonist is presented with an elaborate fanfare:

I was brought in on a palanquin

made of the many bodies of beautiful women.

Brought to this place, to be examined,

swaying on an elephant: a princess of India.

She’s “brought in” (zero agency) on a carrier luridly constructed of beautiful (but presumably judged inferior) female bodies, and though she may feel power-dizzied in the middle of that pompous-and-circumstantial elephantine-careening hullaballoo, what’s actually happening is a simple transaction. She’s being presented for corporeal inspection to ascertain if she’s flesh worth possessing. This prize horse motif gets hammered home (in what is for me the song’s killer line):

Do you know why my ankles are bound in gauze

(sickly dressage: a princess of Kentucky)?

She’s bewildered to find she’s not actually that crowned and gilded jewel-dripping Orientalized bride, but after all just a kept and broken mammal, a half-hearted show-horse whose ultimate adornment is a gauze manacle, even a yellowing bandage (dressage conjures dressing), the mud-splattered mummification of a thoroughbred’s slim ankles ("dressage" might also be a play on dresses as in gowns and "dressing up"). She’s herself become the “poor old nag” of “No Provenance” (not my fave song), ridden until broken, then abandoned to pasture. This is the fate that awaits the album’s protagonists, who are complicit in their own shrinking, who draw contracts around their own contraction, who reduce their power to their potency to seduce, and who become content with being kept, with existing as treasured trinkets until they’re rubbed of their trumped-up luster and are abandoned.

The record’s last song—“Does Not Suffice”—really rams it home (but with a twist). Have One On Me is a big-time “break-up album,” and she describes the final uncoupling strangely, beginning:

I will pack all my pretty dresses.

I will box up my high-heeled shoes.

A sparkling ring, for every finger,

I'll put away, and hide from view.Coats of boucle, jacquard and cashmere;

Cartouche and tweed, all silver-shot—

And everything that could remind you

Of how easy I was not.I'll tuck away my gilded buttons;

I'll bind my silks in shapeless bales;

I’ll wrap it all up, in reams of tissue,

And then I'll kiss you, sweet, farewell.

All of these “I wills” lose their pith and moment and are followed up with lingering entailments of frippery. And then there’s the last verse—she starts it out with this ultra-tragic reverie:

I picture you rising, up in the morning:

Stretching out on your boundless bed,

Beating a clear path to the shower,

Scouring yourself red.

And then, after this vivid picturing of her uber-subject-y, electrically vigorous and swingingly untethered stretching-striding-scrubbing ex, her own “presence” is imagined as an unnoticed absence:

The tap of hangers, swaying in the closet—

Unburdened hooks and empty drawers—

And everywhere I tried to love you

is yours again,

and only yours.

Followed by a minute and a half of “la la”s and a hymnally simple melody disintegrating into cacophony. It’s so lonely. The dude’s free at last, released to go forge his own selfish man-path and be done with his increasingly tedious gf. The speaker’s Big Action has merely been the removal from his realm of her own ephemeric and decorative frivolities. Her wardrobe, which has served as the essential extent of her self-hood, consists of metonymic costumes which were ultimately nothing but clutter in his own spare and echoing spaces, zones she tried and failed to inhabit. Though she’s moved out he’s moved on, and while he’s singing in the shower she’s left reflecting her own nonexistence, that has all the gravity of an emptied wardrobe, gaping vacant save for her unheard, unnoticed, and unmourned phantom quietly tapping clothes hangers.

But here’s the humdinger—it’s really all about “how easy [she] was not.” She’s played the courtesan, decked out and bound herself in the trappings of her femininity, then breathed too much of her own perfume and began to believe the disguise, to think that her self was the thing she could see in the mirror, and that being an object was fine as long as she was possessed, held, kept. And course this “expendable” way of existing would eventually be expended. How much of her grief was, not for the break-up itself, for what she had allowed herself to become, hungry ghost trapped in the mirror of the empty armoire?

Such was my own struggle for a handful of years—no regrets though. I’m left with a lot of beautiful clothes (thanks to what was my void-palliating shopping obsession), and through this long process of self-reduction I did end up with an eventual clarity. I’m clearer and stronger now, and really I think a lot of that process was about becoming more of my adult self.

I’m going to get into that stuff again later down the page, but I feel a twinge to briefly disclaim. I don’t mean to over-vilify my ex—he’s a fine person, and while I did undergo some suffering during our time together, he wasn’t malicious or wicked, and it all ultimately fostered growth. I wasn’t “easy” either—think an anvil wrapped in a boa—and I don’t want to overstep with the post-mortem-izing, but as Joan says

We tell ourselves stories in order to live…We live entirely... by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria — which is our actual experience.

This piecing and puzzling and narrativizing and story-ing and bloggifying—it’s like a whole thang.

Back to the image stuff—I’ve been thinking on the pictures I take, why my eye likes what it likes. Though it sounds overblown I make an effort to preserve my way of looking as much as I can. I know there’s so much (disgustingly) beautiful content on Instagram, but I follow mostly people I know, partly because I’m AR about getting to every picture on my feed (and it’s already overwhelming with only a hundred and some “followings”), but also because I know I will inevitably absorb whatever I see into my spongy eyeballs and will begin to shoot accordingly. I’m a human being in the world and am (and have been) of course endlessly deluged with pics and other media, but I try as much as I can to avoid saturating myself on the daily.

In the vein of visual influences, I know that my passing acquaintance with the Art History canon informs many of my own aesthetic preferences and photographic decisions, and I'd imagine it's prob a collective consciousness situation among many photogs. I really enjoy photographs that feel like or allude to paintings.

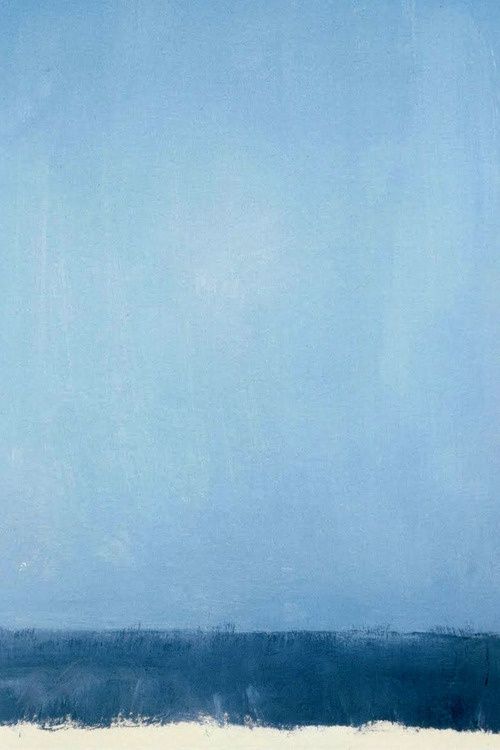

I enjoy my landscape fotos that remind me of abstract paintings—Rothko’s a gimme:

There are also Pollock’s fractals, like looking up into silhouetted tree canopies:

I also like landscape photographs and nature snaps that give a sense of a grand design, that highlight an organized kind of line, present a symmetry, and/or recognize a harmonious graceful palette.

Or naytch and landscape fotes that appear trickily two-dimensional or abstract so your brain gets turned around about what it is you’re looking at

I love this picture of what was my favorite tree at Lake Merritt, a gargantuan old yuke, which was uprooted and blown over in a freak windstorm. The only non-bummerish thing about it was I was able to photograph its high-up branches from an up-close sideways perspective.

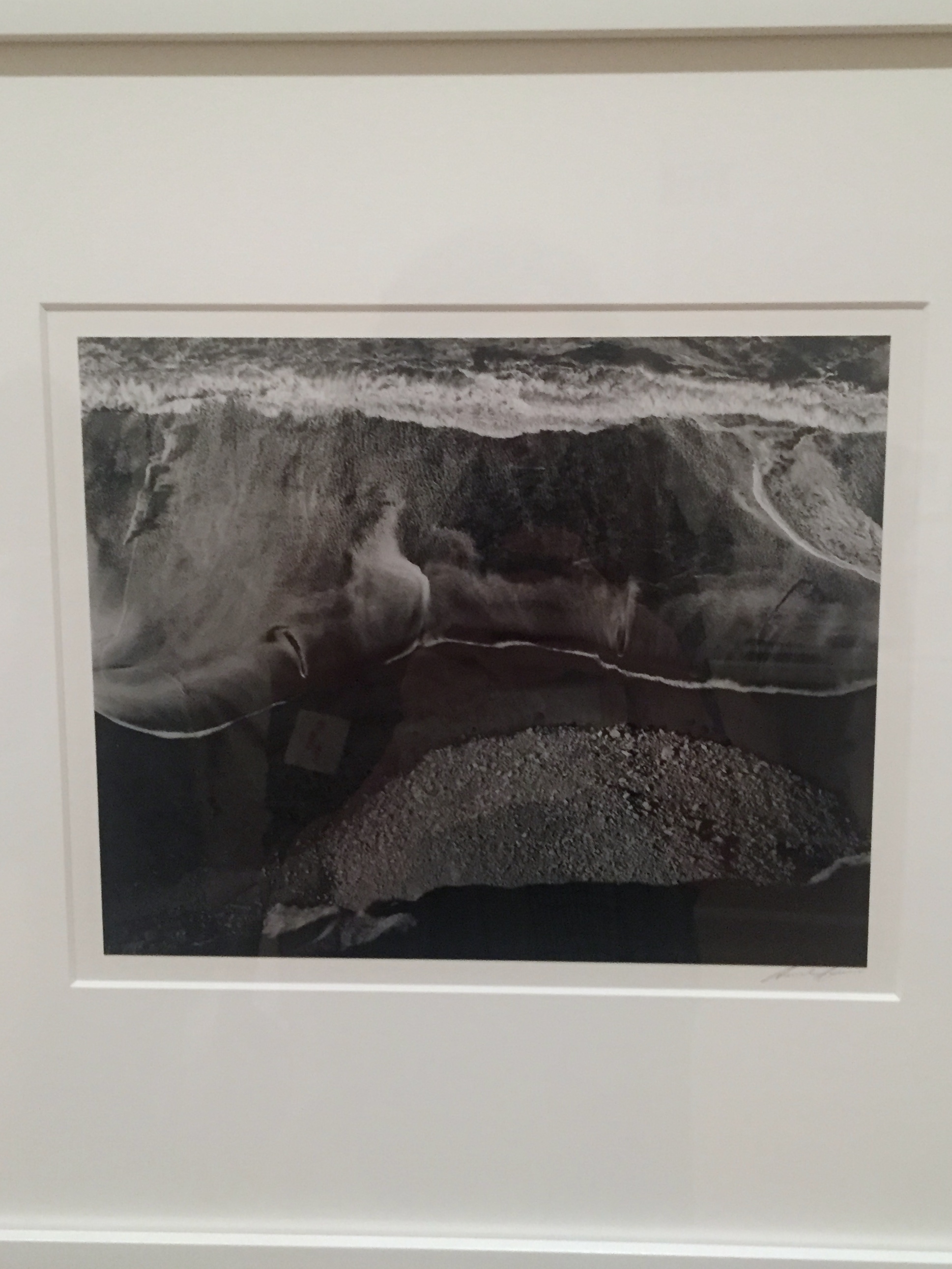

I'd taken this shot at Muir beach and found it fascinating, and felt very #yeahbro when a few months later I encountered some similar stuff at the so-fresh-and-so-clean-clean SFMOMA.

Forgive my reflection, but you get the idea.

In paintings I have always preferred portraits to landscapes (though my position is softening), and when it comes to portrait-type photographs of people I prefer them to feel a little like formal paintings—with, for example, a Da Vinci crop,

a Caravaggio contrast,

a white-lighted Vermeer "VSCO filter,"

or a Rembrandt soul-glimpse.

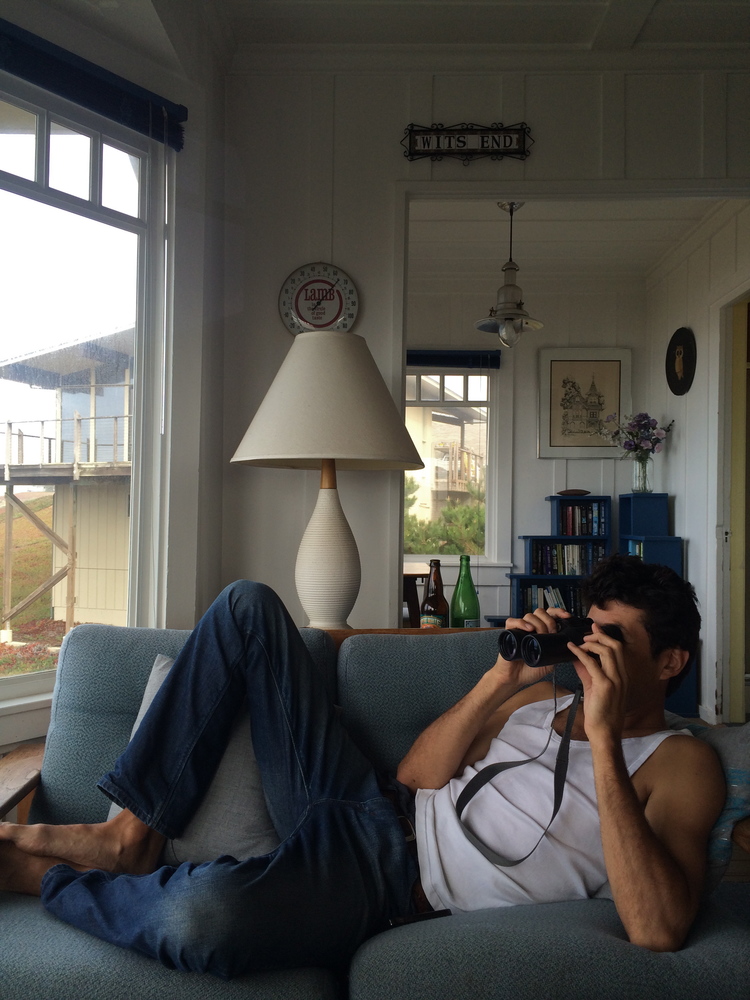

Achieving that fleeting Rembrandt-y seeing is I think one of the aspirings when you’re photographing a human subject. Because (and I’ll get into this a bit more) I’m not especially comfy intruding on the privacy of strangers, I mostly shoot loved ones, and fortunately they’re so accustomed to my omni-present camera they’re not too affected, and either ignore it

or look past it to me, so what I end up with is a picture of “us,” of them seeing me.

I like photo portraits too that are more meta and posed, where the subject is “sitting” in the classical sense. There’s something about the direct eye contact Mona Lisa smirk, or alternately the ponderous three-quarter-view horizon gaze, the subject centrally framed in the formality of good light and clean composition, that points to itself, makes no bones about the mutual exchange of a taken picture, and so feels honest in its unashamed affectation.

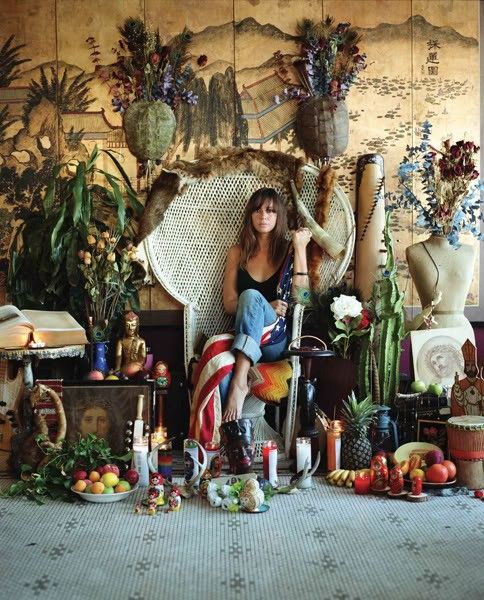

I also love the official, commissioned vibe of the en-portaitured, throned surrounded by symbolic objects and evocative flora and fauna (both dead and alive), which is part of why the Joanna Newsom Ys (2006) album artwork got my D so hard.

I was zinged similarly by Lorde's 2013 debut album's original artwork,

and was also struck coming upon this 2006 photo of Chan Marshall (/Cat Power),

which in turn hearkened strongly to Have One On Me's Joanna odalisqued in the middle of all her trinkets and oddities and strewn-about finery (I know I'm obsessed).

These images are so meaty for me—female artists at the top of their game, self-mythologizing like modernists, themselves crafting and micro-managing the presentation of their form, surrounding themselves with all their woman things, overlaying their self-portrayals with symbolism and even a slight, wry irony. I want to preserve the tingle of perceived meaning so I won't over-think it right now, but I find them tremendously inspiring and have held a long-standing notion to make some portraits in a similar style (I used to fancy I'd make little paintings, but now I'm leaning toward the less ramshackle and unskilled option of setting up some photes).

Listening to the car radio the last time we were in So-Cal I got grabbed by Adele's maddeningly catchy "Send My Love." Back at the casa I youtubed it to hear it again (and again, and again), and I was positively arrested by the visuals of the video. Adele stands center-stage-lit in blackness, wearing a queenly floor-length floral Dolce and Gabana gown, hands clasped on her right hip, staring and blinking straight at the camera in a fashion I'm certain Tyra would grade "fierce." As the song starts the camera zooms in steadily, but then the image starts to morph. You feel for a second like your eyes are having trouble focusing until it becomes clear there are two Adele's moving differently, overlaid over each other. The selves multiply, move apart, recombine in ways that are almost reminiscent of Samsara's Thousand Hand Guan Yin. It's mesmerizing and wildly dynamic, all these varyingly tinted dancing Adeles,

who at the song's conclusion finally recombine into one single coolly-lit unmoving woman. I'm not actually the biggest Adele fan—not that I dislike her, but she doesn't generally captivate me. This vid however blew me away, and worked perfectly with the sentiments of the song, feeling slightly haunted by the final malingerings of a very past love, but knowing that a "we" (ostensibly she and her ex, but also perhaps her own many selves) "have got to let go of all of our ghosts."

It reminds me so much Joanna's "The Things I Say" off her now year-old album Divers, which features this section:

When the sky goes pink in Paris, France,

do you think of the girl who used to dance

when you'd frame her moving within your hands,

saying This I won't forget?

What happened to the man you were,

when you loved somebody before her?

Did he die?

Or does that man endure, somewhere far away?

Our lives come easy and our lives come hard.

We carry them like a pack of cards:

some we don't use, but we don't discard,

but keep for a rainy day.

The song ends with the eeriest chorus of saws and then a couple lines of vocals reversed, which turned back around is apparently a couple of "make you any friends" and a "somewhere far away" (lyrics from elsewhere in the song).

Divers is an incredibly dense and complex piece of work, but one of its motifs/concerns is the idea of multiple selves (one way Joanna expresses this is by using only her own voice on tracks with back-up vocals), all existing all at once on the continuum of time, and possibly in infinite variations on numberless alternate planes throughout the limitlessness of space.

The idea of multiple selves is tremendously riveting to me even in its most literal sense—that as socialized humans we are to a degree different people with different people. We read the crowd, or put more gently we learn from the start how to please and engage, how to meet people where they're at, how to connect where the connections are. Like all things it's about balance (I learn this more and more as I get older)—we don't want to be spineless or conniving serpentine sycophants, but we also don't want to be insensitive, tone-deaf, selfish, narcissist weirdos.

Then there are all our different "I"s we've been throughout our lives, all our ages and their joys and loves and fears and trials and traumas and coping mechanisms—"they dwell in us" (like Milosz's "moments from yesterday and from centuries ago," but the possibility of past lives is a whole other other I'm not going to get into here). I did some super-powerful therapy around this "inner child" stuff, where I held a pillow in my lap and pretended it was little me, at a knobby-kneed age where I had in no way been equipped to deal with the shit that had been going down around me, and then adult Molly held little Molly, and told her that it was all right, that she had carried a lot and that she'd done well, that it was okay to feel sad, all that kind of thing. It was some of the most absolute compassion I've ever given to myself, and was both heart-breaking and deeply healing. I'd recommend this kind of work to anyone—we've all experienced pain we were too young to process, and these hurts can become frozen and preserved inside us, can continue to hurt us long after the danger's passed. It's so important to let the air in, to feel the feelings we've been scared to, to look at what happened through our adult eyes, and to begin the healing and the eventual letting go.

Bringing it back home: the Adele video reminded me of how I salivate over double-exposure photos; these ones my friend Rebecca Schwartz collaborated on with her pal Yoni Kifle are drop-dead gorgeous.

They're so lovely (and very in keeping with the "all of our ghosts" vibe amirite). I hope to learn how to take double-exposures someday; I tinkered a little with an app but had whatevs results (probably my fault, not the technology's).

(These actually are two subtly different images, with one flipped.)

Mirrors can create a similarly satisfying effect,

almost feels like the "Two Fridas."

So, we all have multiplicity (and at our darker moments duplicity); we are large, we contain multitudes. My sense though is that at the heart at of all these dancing selves we need to have integrity (a wee bit o’ wordplay for you there), a sense of a single, singular self, or, put another way, of our own soul.

There's a lot of talk about finding oneself—it's a curious phrase, when you get past the basic-ness. A lot of people feel lost, maybe particularly at rocky points in their lives, or maybe less circumstantially and more in terms of their innards. I do see a lot of folks failing to choose truth, inundating themselves with twitchy stimulation instead of making the effort to be still and present, feeding their egos instead of nourishing their souls, seeking the quick glitzy fix instead of performing the slow and unglamorous work of self-repair, accepting counterfeit, sacrificing thoroughness, floundering, fleeing, fearing. It's a complicated time, I appreciate, to be. Reality is wobbling and warping—there's so much. But these struggles aren't new—the Temple of Apollo at Delphi's forecourt sports the inscribed aphorism: γνῶθι σεαυτὸ—"know thyself." To know oneself I think is to ultimately, inevitably, love oneself. I believe the deepest parts of us are really good, really beautiful, really worthy of love, and I think we're all parts of the same good beautiful lovable thing. In our lives I think it behooves us (by extension all of us) to try to find what makes us feel whole, to refrain from corner-cutting, to be kind to ourselves and others, to take the high roads, to endeavor to get centered up, to be generous in thought and action, to permit ourselves to slow down and chill the fack out, to try to be grateful, positive, and present (this one's hardest for me). It's daily work, but as with all exercise, the practice becomes less willed than reflexive.

Back to proper-like portraits for a mo—my old co-worker Georgia had paid me the compliment of peeping my website, and made the curious observation that in my collection of animal pictures I often shoot animals with the compositional dignity and decorous respect afforded human subjects. I was struck by accuracy of the observation, and since it's mostly in pet pics that I see this I don’t feel like I’m overmuch trying to domesticate the wildness with my anthropomorphizing.

I am less familiar with capital-P Photographers than with Painters, but two I’ve looked at a lot are Henri Cartier Bresson (who I mentioned above) and, more recently (for the world also), Vivian Maier.

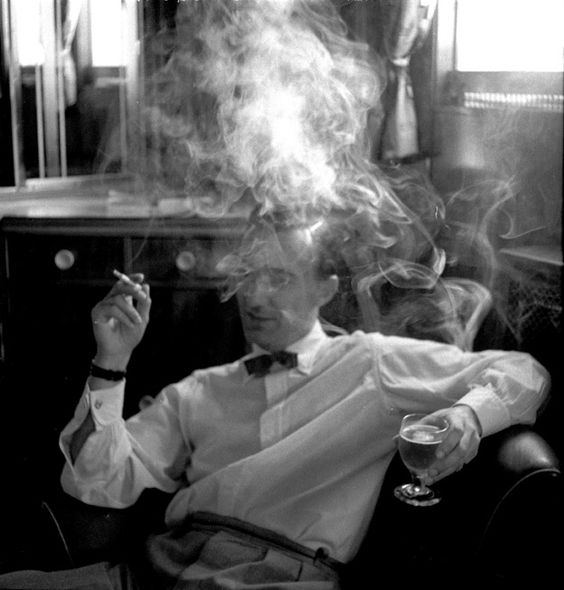

They were both strikingly gifted photogs, and the images they produced are arresting and simple, multi-leveled and complex. Given my own proclivities I get totally bonerized by all the fog, smog, smoke, shadow, blur, and reflection in their fotes; these shrouding withholding motifs are for me incredibly compelling (which is why I myself take buttloads of mist pix).

Cartier-Bresson.

Maier.

Maier.

Cartier-Bresson.

Maier.

Maier.

Cartier-Bresson.

Free-associating here—you know how I be—I am reminded of those favorite Sylvia Plath Ariel metaphors I’ve mentioned previously—all deflecting clouds and reflecting pools and grey and glassy seas.

So, I have a thing for cloaking, curtaining elements in photos—in poems—and in life also; since the "capturing" (some photog vocab is so loaded with implication) and pinning down of reality is an assumptive audacity that is implicit in the act of taking a picture, and since existing (and reveling) in mystery feels a lot better to me than trying to fix experience into certainty, I get goose-bumped by these visual obfuscations in photographs.

It makes sense then given my penchant for “veils” that I don’t always prefer photographs of people’s faces. And I really, really don’t like photos that are taken without their subject’s permission—I took one such on BART because I loved the lines and light, and I still feel kind of gross about it.

Maybe it’s the sometimes sneaky, definitely ubiquitous naytch of cameras these days, but I am put off by the genre of pictures taken by people of people(s) they don’t know, specifically when race and poverty and “the exotic” are in the mix. Some of that nat ge-O-the-Humanity shit really rankles me, partly because it’s so self-congratulatory and partly because it has an undercover infantilizing and fetishizing vibe: These simple pure people are so joyful and wise in their impoverishment! We have so much to learn from this deep gaze, this wide grin! Ugh. These images seem to come from a carnivorous eye, to violate the contract of balance, equality, and trust that seems to me requisite if one is to “take” a photo of another.

I’m sure this isn’t always the case, and that the feeling is informed partly by my own introverted way of being in the world. I like to pay unknown people the respect of privacy and space in public places, and appreciate receiving the same treatment. If I have strangers in my pictures it’s likely at a distance—I don’t pretend that by pointing a camera at a person I’m bridging a gap, and prefer in this context the visual of the human form from the more archetypal afar.

Counterpoint: Bresson and Maier are both street photographers. I’m trying to figure out why this in their shots doesn’t often bother me. Partly I think it’s the fact that photography was a rarer thing in their times, unlike today when every schmo del mundo is packing an iPhone (and you can’t swing a selfie stick without knocking down five others).

I like Maier first and foremost because she’s so fucking good. If you’re not familiar treat yourself to a googling, or check the doc Finding Vivian Maier (which que suerte is streaming on Netflix).

Maier took loads of pics of street strangers; the ironic effect, however, of her sneaky Rolleiflex, a camera whose viewfinder she peeped from above to snap half-clandestine shots from the waist, is that her subjects are endowed with the dignity of being shot from slightly below the chin, giving them the appearance of a resistant, stubborn, and defiant self-hood. It doesn’t look like she “caught” or "captured" them on film—if anything they’re often imperiously staring her down, the upward angle on their faces creating a skeptical effect, or even the faint flavor of a sneer.

Maier is often in these shots a suggested secondary subject—you can feel her lurking at the window of the lens. She gets meta with it sometimes, including in shots the watching ghost of her own reflection,

or her ominous shadow creeping into the frame.

I was so stoked to come upon the picture above since I've regarded the photo below as one of my faves of my own.

Maier's pictures don’t feel like they have problematic power dynamics with their subjects—she isn’t a collector or a conqueror, but rather a weirdo and an outcast. Her shots show the alienated gaze of the perpetual outsider, or caricature the adumbral encroachment of the contact-starved stalker. I feel that in these moments Maier is exploring the problematic aspect of “making art” out of the lives of others.

Any time a person makes art out of another person it is in part a fraught and cannibalistic action. It makes me think of Robert Hass’s poem about his brother’s dying “August Notebook: A Death.” He begins “I woke up thinking about my brother’s body," and goes on to describe his imagining his brother laid out in the mortuary, and then continues

When I woke, I visualized this narrative

and thought it would be shorter. I thought

that what would represent my feelings

would be the absence of metaphor.

It’s so discordant—he’s basically rubbing his own nose in the fact that his brother has died and while his body's stretched out dead on a slab, he is himself sitting at a typewriter using it. It’s not that he isn’t genuinely grieving—he loved his brother—it’s just significant to be aware of when one's art's material is composed of the life (or death) of another being.

It reminds me of another moment, in David Sedaris’s haunting and hilarious (when is he not these things?) essay “Repeat After Me.” I’m going to include a huge chunk because it’s brilliant. Loads of Sedaris’s writing is about his family—in this instance he’s hanging with his sister Lisa.

We stopped for gas on the way home and we're parking in front of her house when she turned to relate what I've come to think of as the quintessential Lisa story. "One time," she said. "One time I was out driving." The incident began with a quick trip to the grocery store and ended unexpectedly, with a wounded animal stuffed into a pillowcase and held to the tailpipe of her car.

Like most of my sister's stories, it provoked a startling mental picture. Capturing a moment in time when one's actions seemed both unimaginably cruel and completely natural. Details were carefully chosen and the pace built gradually. Punctuated by a series of well timed pauses. And then. And then. She reached the inevitable conclusion and just as I started to laugh, she put her head against the steering wheel and fell apart.

It wasn't the gentle flow of tears you might release when recalling an isolated action or event, but the violent explosion that comes when you realize that all such events are connected, forming an endless chain of guilt and suffering. I instinctively reach for the notebook I keep in my pocket.

Boom.

And she grabbed my hand to stop me. "If you ever," she said, "ever, repeat that story, I will never talk to you again." In the movie version of our lives I would have turned to offer her comfort, reminding her, convincing her, that the actions she described had been kind and just. Because it was. She's incapable of acting otherwise.

In the real version of our lives, my immediate goal was simply to change her mind. "Oh, come on," I said. "That story's really funny and I mean, it's not like you're going to do anything with it." Your life, your privacy, your bottomless sorrow, it's not like you're going to do anything with it. Is this the brother I always was or the brother I have become?

I'd worried that in making the movie the director might get me and my family wrong. But now a worse thought occurred to me, what if he got us right?

Dusk. The camera pans an unremarkable suburban street, moving in on a parked four-door automobile where a small, evil man turns to his sobbing sister saying, "what if I use this story but say that it happened to a friend?"

But maybe that's not the end. Maybe before the credits roll we see this same man getting out of bed in the middle of the night, walking past his sister's bedroom, and downstairs into the kitchen. A switch is thrown and we notice in the far corner of the room, a large, standing bird cage covered with a tablecloth. He approaches it carefully and removes the cover, waking a Blue-fronted Amazon parrot. Its eyes glowing red in the sudden light.

Through everything that's come before this moment, we understand that the man has something important to say. From his own mouth the words are meaningless and so he pulls up a chair. The clock reads 3:00 AM, then 4:00, then 5:00 as he sits before the brilliant bird, repeating slowly and clearly the words forgive me. Forgive me. Forgive me.

What’s fascinating is that he does in publishing this essay effectively disrespect his sister’s request for privacy—the reader has a pretty good idea of what went down with Lisa’s mercy-killing. David's having his cake and eating it too, but he’s also placing himself on the tightrope above the roiling pit of life and art, kindness and cruelty, good and bad, chaos and meaning.

Henri Cartier Bresson was more interested in street photography than formal portraiture, but I want to very briefly include a couple of his thoughts on more official shots, because I think exhibit his concern with the complex morality of his medium:

A certain identity is manifest in all the portraits taken by one photographer. The photographer is searching for identity of his sitter, and also trying to fulfill an expression of himself. The true portrait emphasizes neither the suave nor the grotesque, but reflects the personality.

And:

If, in making a portrait, you hope to grasp the interior silence of a willing victim, it’s very difficult, but you must somehow position the camera between his shirt and his skin.

As for his preferred street photography, he opted to shoot stealthily, generally feeling that if he was noticed it disrupted the moment of truth he’d perceived in whatever he was trying to capture. I think though, even if he was sneaking pics of strangers, that he operated out of a place of true empathy, humanism, and equality. He said, “One must always take photographs with the greatest respect for the subject and for oneself.”

So that attenuates for me the ick factor—I can feel that respect in his pictures of others. But it’s certainly not his subject matter that makes him my offish fave fotog, but rather the harmoniousness of his compositions, his ability to grab and preserve that elegant moment of form and rightness within movement and disorder. He was durned good at identifying the graceful frame through which he’d patiently, sometimes for hours, wait for life to pass, and when the magic happened he’d strike, and freeze the fleeting. From his book The Mind's Eye: Writings on Photography and Photographers:

In order to “give a meaning” to the world, one has to feel oneself involved in what one frames through the viewfinder. This attitude requires concentration, a discipline of mind, sensitivity, and a sense of geometry–it is by great economy of means that one arrives at simplicity of expression.

I think I might have to include a couple more quotes, because they are so right-on, and express my own feelings far more eloquently and lucidly than I could:

If a photograph is to communicate its subject in all its intensity, the relationship of form must be rigorously established. Photography implies the recognition of a rhythm in the world of real things. What the eye does is to find and focus on the particular subject within the mass of reality; what the camera does is simply to register upon film the decision made by the eye.

And:

We look at and perceive a photograph, as we do a painting, in its entirety and all in one glance. In a photograph, composition is the result of a simultaneous coalition, the organic coordination of elements seen by the eye. One does not add composition as though it were an afterthought superimposed on the basic subject material, since it is impossible to separate content from form. Composition must have its own inevitability about it.

Yassss!!!!

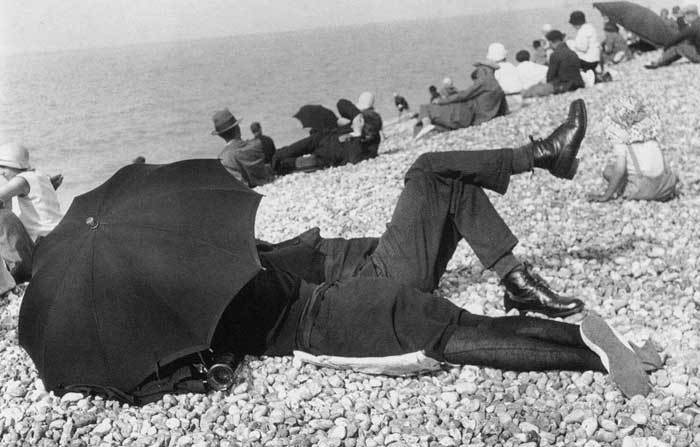

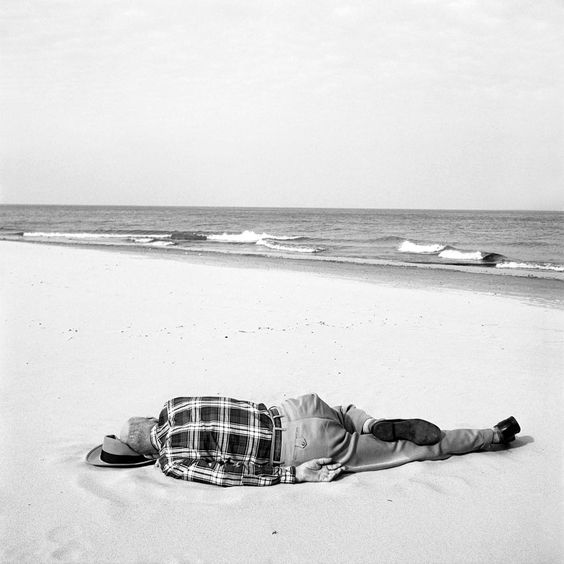

I also like Bresson and Maier for all the times they opt not to show faces.

Cartier-Bresson.

Cartier-Bresson.

Cartier-Bresson.

Maier.

Maier.

Maier.

Maier.

Maier.

Maier.

Maier.

Maier.

Maier.

Scrolling though those gives me such a rush. In my own photos withholding or obscuring the face is something I love.

There is and has been in some cultures the belief that to have one’s picture taken is to risk having one’s soul stolen. This is not unrelated to similar ideas surrounding mirrors, the thought being that when they take our image they take a piece of our spirit. Back to Plath, and her chilling line “The mirrors are sheeted”—there was a practice of throwing bedsheets over all the mirrors in the houses of the recently deceased lest the new ghost be "captured" in one and prevented from passing on to the next realm.

I don’t want to get too obvi and “this day and age”-y here, but mirrors, photos, and souls…there’s some culturally pertinent shit in the mix there with our ever-burgeoning obsession on appearance and the projection of an “image,” and what this fixation on faceting and burnishing our outsides is doing to our stripped and decrepit interiors, the spaces where one might suppose our souls live.

It’s a brave new world with the sohsh meeds, and too early to tell what it will all come to, but I think there are some fascinating things happening around selfhood and these platforms on which we are able to so cheaply construct and project versions of it. It’s an amplification of what I touched on above—the self-presentation in which we all as social animals participate, putting on our “face[s] to meet the faces that we meet.”

I’m not an expert on all the teckmology. I have a generally cobwebby Facebook that I can’t help but despise and use primarily to read Jezebel articles (though I have no idea why I go through the FB to do this—I think it’s the laziness of having the pieces coursed and plattered for me). I’m not poo-poo-ing the meaningful ways the fubs might function in the lives of others—it just isn’t my bag and I don’t feel qualified to analyze it too hard.

Instagram’s my main social media squeeze. I try to keep my usage pretty simple—mostly I share pictures I like of peeps and spots and creatures and moments I like, and I personally enjoy it as a succinct little catalog of the beauty and good times I’m #blessed to witness and experience. I follow, as I said, almost exclusively people I know and like in real life. I also have a handful of accounts I check on the reg but don’t follow because I need to be in a specific mood to view them or I’ll get too irritated.

These are the highly curated VSCO-ed feeds. I don’t want to talk shit on specific accounts—I think we’re all familiar with the aesthetic of these modern-day one-woman lady mags. I will say I find maddening the affectation of a drawl in captions by non-country women, the “this mama” narratives, and the comparably parlanced ultra-hip, ultra-hackneyed employment of the word “babe.” I am sick to fucking death of pseudo-spiritual drivel, and I think it is so insanely blatant that people post clearly phone-timer-ed photos of themselves “meditating” and having “morning moment” “me time” in their Lulu with their steaming cuppas. It’s rancid, but thinking on it now it seems symptomatic of the level of disorder that’s happening around this stuff.

Ballsy also, though less twee and phony and more agro and no-bones, is the selfie-selfie. This piece slams it pretty hard, and while I don’t want to guzzle the haterade I do think there’s an certain degree of narcissism involved in the supposition that people want to get POW-ed with one’s face all the time. Selfies with “make-up filters” are astoundingly weird to the degree that I can’t even take them seriously enough to get feministy and fired up. You can tint and polish your skin with all kinds of alien-esque glowy filters, brighten and re-size your eyes, whiten your teeth, make yourself skinnier (por supuesto), make yourself taller, and who knows what else. The results can be creepy and tacky af, but just as people can have “good” or bad plastic surgery I’m sure some people are using these appearance-editing tools skillfully enough that I don’t even pick up on it. Good for them?

Really though, I don’t care what works for other people, and I hope they’re finding ways to love themselves amidst all the madness and the crap, holding fast to the cognizance they’re so much more than the quick-and-dirty, archly commodified representatives comprising their online self-offerings. It’s really neat that so many individuals, thanks to the ease and expanse of exposure afforded by platforms like Instagram, have been able to swing becoming real-life “working artists”—“makers” who get paid. I love that. It’s just a tricky business, this commercialization of self, folks obsessing on their insta-stats like they’re graphs in a boardroom, consumed by the drive to dial in their own “likes-ability” until their output is diminished to sterilized soulless plastic trash (and shallowness and palatability are indeed probable recipes for at least some modicum of “success” in our lazy, sloppy, deadened consumer culture). Ah well we all find our own ways to navigate—I truly wish for all varieties of peeps to find their fullness by whichever ways are workable for them, even if their value systems are harder for me to find the merit in.

So, as for my own aesthetics and preferences, I am most compelled by pictures without faces, both generally and also when it's my own form in the frame.

I’m not comfortable in front of a lens—it makes me feel squirmy, and my visage tends to tense and show my mild discomfort. Beyond that I have a mobile face—my Dad’s is the same way. We’re both animated speakers, and have a particular clay-like quality to our features when we talk (which we usually are). This makes for some really funny contorted rubber-expressioned photos—we just don’t have those still, planed bones that translate best into pictures (my mom, Maddy, and Rama do). When I see video of myself it makes a lot more sense than odd moments frozen in photos.

It goes lots deeper though than the vanity-aspect. As a redhead my appearance has always received attention—when I was a baby my aunt on outings with my mom and me would tally the number of people who stopped to comment. Like most kids I was indifferent to my appearance and took the approbation with a grain of salt (except I remember once in preschool being extremely pleased when someone told me I just looked like Ariel of The Little Mermaid.) I’ve always loved “fashion” in one way or another (then it was barbies, paper dolls, and dress-up), but I was a totally tomboyish grubby tangly-haired hooligan, ever trying to negotiate my way out of baths and crying dramatic tears when my mom, cursing, tried to move a comb through my snarled waist-length rat’s nest.

It seems integral to female self-esteem to get some of these years totally free from caring about one’s looks. The world’s only too happy to tell you that your worth can be measured in the mirror, and I can’t imagine how shite it must be to “grow up too fast,” to never have the time to make and put away a nest-egg of self-love and self-hood before society thunders in to tell you you’re so much less. Today’s preening, hair-straightened, styled-to-the-nines six year-olds really bum me out.

I resisted the “growing up” as long as I could (which meant pushing back against the transition to not dressing like a slobbish little geek) before I finally gave into the first stage of womanhood and began to put some intention into my presentation. I over time experienced some development around all that jazz (that I wrote about a bit above), and though I care now about what I wear, I absolutely dress for myself. I have always loved fashion—now I enjoy it on my own body. And that’s a’ight. Rachel Shukert had some thoughts on this I’d noted a few years back (with less pertinent bits omitted with ellipses):

Femininity is not the enemy; misogyny is…There’s nothing wrong with being a jeans-and-t-shirt…kind of girl. The problem is when her lack of interest in her appearance becomes a sort of shorthand for why we should love her. Because she isn’t into girly things like clothes, which are stupid, because girls like them…It’s like the conventional wisdom that its much, much worse to be called a “cunt” than a “dick,” because while they are both crude terms for human genitalia, obviously the female one is so much more insulting, because of society’s underlying insistence that the simple, ontological fact of womanhood is an infinite source of shame.

Right on. We have no choice but to exist in a body in a world that cares way too much about our bodies, and we all form our own strategies to survive and thrive. So I talked about Have One On Me’s exploration and my own growth around this appearance and self-presentation stuff—my first adolescent maturation (caring more) and my “adult-ish” one (caring less). My friend Emma’s mentor has talked about being a double-agent—presenting as a “put-together” “attractive” woman gains you admittance to male zones, and once you’re there you can bust up the patriarchy from the inside. You can wield your femininity insidiously, make a weapon of the world’s underestimation and dismissal of you. I’m not an aggressive person, but I hold my own space, which isn’t always immediately apparent to people. My reserve (in certain contexts) and pleasant courtesy can be misread as weakness and as an invitation, particularly by bullies. I sort of love to, when I get fucked with, flex the iron fist in the kid glove. I find it immensely satisfying to explode people’s prejudices simply by being my own exact self. And I like showing what of myself I want to show when I want show it, and I prefer to keep much of myself to myself.

This is I think the biggest part of why I prefer the pictures I “put out there” to show the back of my head—I don’t want to give them my face. I like to present the exoskeleton, to remind the viewer of all that’s hidden. The world thinks it’s entitled to the female form—I turn my back on that. I don’t want to grant the viewer my gaze, the illusion of my interest. I like them to see it directed away from them, to remember that we’re all viewers, all acting subjects, not just subjects of a photograph.

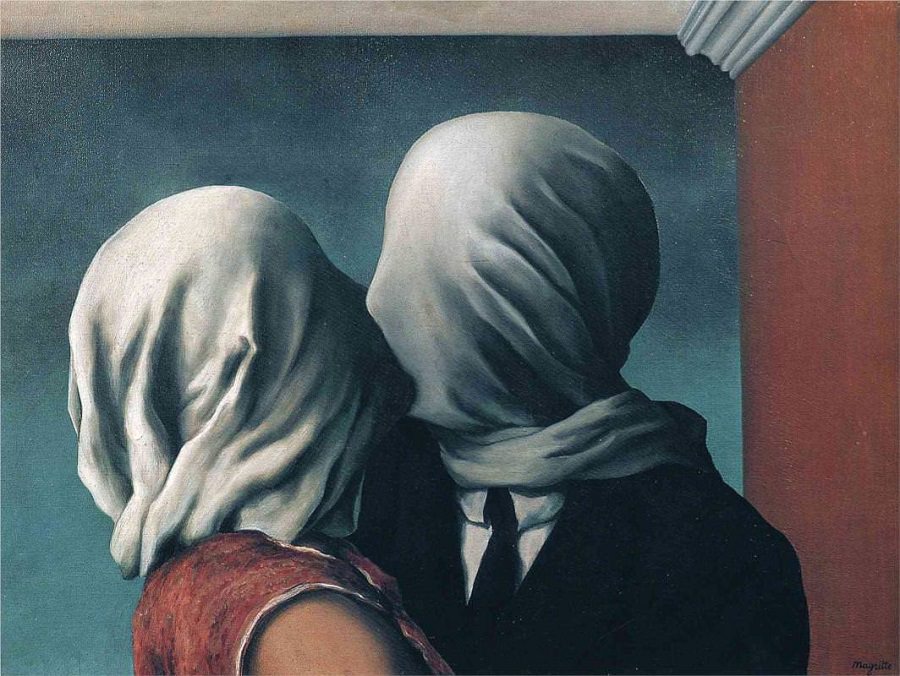

I like this in photos of other people too—I am compelled by the humbling reminder of unknowing. I was always fascinated by Magritte’s veiled “lovers”

(though, eerie bit of context: his mother when he was fourteen had drowned herself and was found, days later, with her nightgown tangled around her head).

There’s something there. People always want to “get” other people, to nail them down in one way or another. My ex, I felt, approached other people in terms of what he apprehended their place to be on the power ladder—above him or below him—and conducted himself accordingly. Throughout our relationship I felt compelled to show him, again and again, that he wasn’t above me (nor below me in his more self-deprecating, acolytical swings), that I was a person, and that he didn’t "have" me.

I’m so glad to have now found a partner who is capable of having co-autonomy with me, who doesn’t carry a need to “have” or “be had.” To paraphrase my Dad’s possibly mis-remembering Sartre (because I cannot for the life of me locate the quote on the googs): “Every man is more than he seems.” I love not having Rama. I have on my website a Rommer album (these days I photograph him as much an anyone), and there’s sequence of faceless photos that feels just right.

Brief aside: my friend Allie May (who is a heart-stoppingly amazing artist) had asked me on a Mount Tam hike why the no-face? I hadn’t had a coherent answer at the time, but she said the photos reminded her of the faceless Waldorf dolls (she joins the handful of ‘dorfs with whom I’ve had instant soul recognition—then others being Biz, Lizzie, Emma, and of course Rama), which are aimed to foster children’s imagination. This association was interesting to me, though I don’t know exactly how it relates to my own analysis.

In addition to general facelessness, I am visually stimulated by a kind of picture I’ve (o-so-cheekily) coined (and collected as) “from the back” photos—where a figure is positioned (oftentimes) in the center of the frame with his/her/more-often-than-not-my back to the viewer.

I remember slamming a couple a few years back and thinking bingo! I’ve taken or collaborated with Rama on taking (for better or worse the nicely-clothed female form makes for a more archetypal image than a trucker-hatted male one) many of these sorts of pictures since. I was, after becoming more versed in Instagram aesthetics, a bit bummerized to tick that this composition was prevalent to the point of being a cliché.

Whenever I get smacked with my own unoriginality I am laughingly reminded of a glorious David Sedaris moment from The Santaland Diaries:

I went to a store on the Upper West Side. This store is like a Museum of Natural History where everything is for sale: every taxidermic or skeletal animal that roams the earth is represented in this shop and, because of that, it is popular. I went with my brother last weekend. Near the cash register was a bowl of glass eyes and a sign reading "DO NOT HOLD THESE GLASS EYES UP AGAINST YOUR OWN EYES: THE ROUGH STEM CAN CAUSE INJURY."

I talked to the fellow behind the counter and he said, "It’s the same thing every time. First they hold up the eyes and then they go for the horns. I'm sick of it."

It disturbed me that, until I saw the sign, my first impulse was to hold those eyes up to my own. I thought it might be a laugh riot.

All of us take pride and pleasure in the fact that we are unique, but I’m afraid when all is said and done the police are right: it all comes down to fingerprints.

So be it.

Like your average basic soer quiche PNW beanied-babe I too savor being in nature, and for me landscape pictures are often enhanced by the presence of a human form, even if only to give scale. Beyond that it adds interest, creates a focal point—I’m sure there’s some golden ratio stuff too that’s way beyond my ken.

More impressionistically, positioning the figure in the center of the frame replicates the feeling, for me, of being at the center of one's life, or centered even. The world surrounds our smallness, but if we hold gravity in our self-hood, give value and respect to our own subjecthood, it allows us perceive it all as experience orbiting our own protagonism. There’s something kind of humbling about it too—this pointing to the act of looking, both by the viewer in the photograph and the viewer of the photograph. We’re all tourists, as they say, passing through, taking it in. There’s a compelling stillness then in the center-framed, fixed subject caught in the moment of beholding, a sense of an eternal present superimposed on the backdrop of transience. The photographic subject in her/his from-the-back at-a-slight-distance anonymity transmutes into archetype, acting as our stick figure envoy to those many places "commensurate to our capacity for wonder" on this vast and bafflingly lovely planet.

It's funny, I have my schooldays reflex to wrangle it all back together in this my concluding paragraph, and looking back over this sprawling thing I do detect one clear theme: my photographic preferences seem to directly reflect my systems of belief (or at least areas of perceived meaning and suspicions of Truth). I'm bored though at the notion of lasso-ing it up into a neat list of takeaways, so let's leave it here at these near nine thousand words, worth I can't tell how many pictures.